A Going-to-Patagonia Time ADHX 45

A gravel bike for Patagonia, a magnifique Time ADHX 45 frameset and the latest Regroup Custom build to ride in the wild.

March 6, 2025

visibilitySATURDAYS >> JOIN THE REGROUP COFFEE RIDE

closePEOPLE

As a rider, pitting yourself against the bunch takes confidence, guile and a keen sense of purpose. And it’s no different for brands. Just ask Time, an industry outlier that’s always ridden its own race.

Drive, oh, about an hour, from Vienna, Austria, point your nose towards Slovakia, and with a bit of luck and a dash of cycling serendipity, you’ll arrive at the door of Time Bicycles, the oldest and largest-scale composite bicycle factory in Europe. We know this because we have Tony Karklins, Time’s CEO, to hand - well, to Zoom - who is speaking to us before he hops on a plane to get to said factory. “It’s very well located,” says Tony, of Time’s home base. “It’s inside the automotive zone to the northeast of Vienna, where brands like Porsche and Audi produce. There’s really nothing we can’t source or have provided to us that isn’t within a pretty tight radius of the factory.” It’s a lucky place to be. Although luck, as it turns out, has very little to do with Time’s story.

“Time was a proud French brand,” explains Tony. “The Slovakian facility was established in 2003, but Time was founded in 1987. As they grew, they had to open a sub-factory. So they had a decision to make: go to Asia, as 99.9% of the bike industry would, or stay in Europe and find a place close to home with competitive production costs. Roland Cattin, who founded Time, was the outlier in the whole industry. He chose to keep Time in Europe.”

A brilliant decision in hindsight. At the time – pardon the pun – ridiculously brave. “Oh man, it was so brave,” says Tony, shaking his head in wonder, “and that’s why I’m so proud to be part of the Time story. It was a painful decision and probably didn’t make much sense to those around him, but as the years rolled on, Roland’s choice started to look better and better. Time remained a maker in full control of its product, not a marketer of bikes built by someone else, far-removed from everything that made it special, materially and culturally.”

Forks in the road. Go left, go right, different destinations. We can’t imagine Roland got invited to many parties back in the early 2000s, not by his fellow bike brands anyway, who you would hope might feel a tad embarrassed for selling out their manufacturing base and workforce so easily, later framing their decision as the only one they could have made in the face of the exodus to the Far East. Roland’s left turn would have made for some uncomfortable buffet talk.

So, where does that leave Time today? “We have this super-refined technology, manufacturing in one of the most strategic spots in Europe. The only challenge we have now is to share our story with more cyclists,” enthuses Tony.

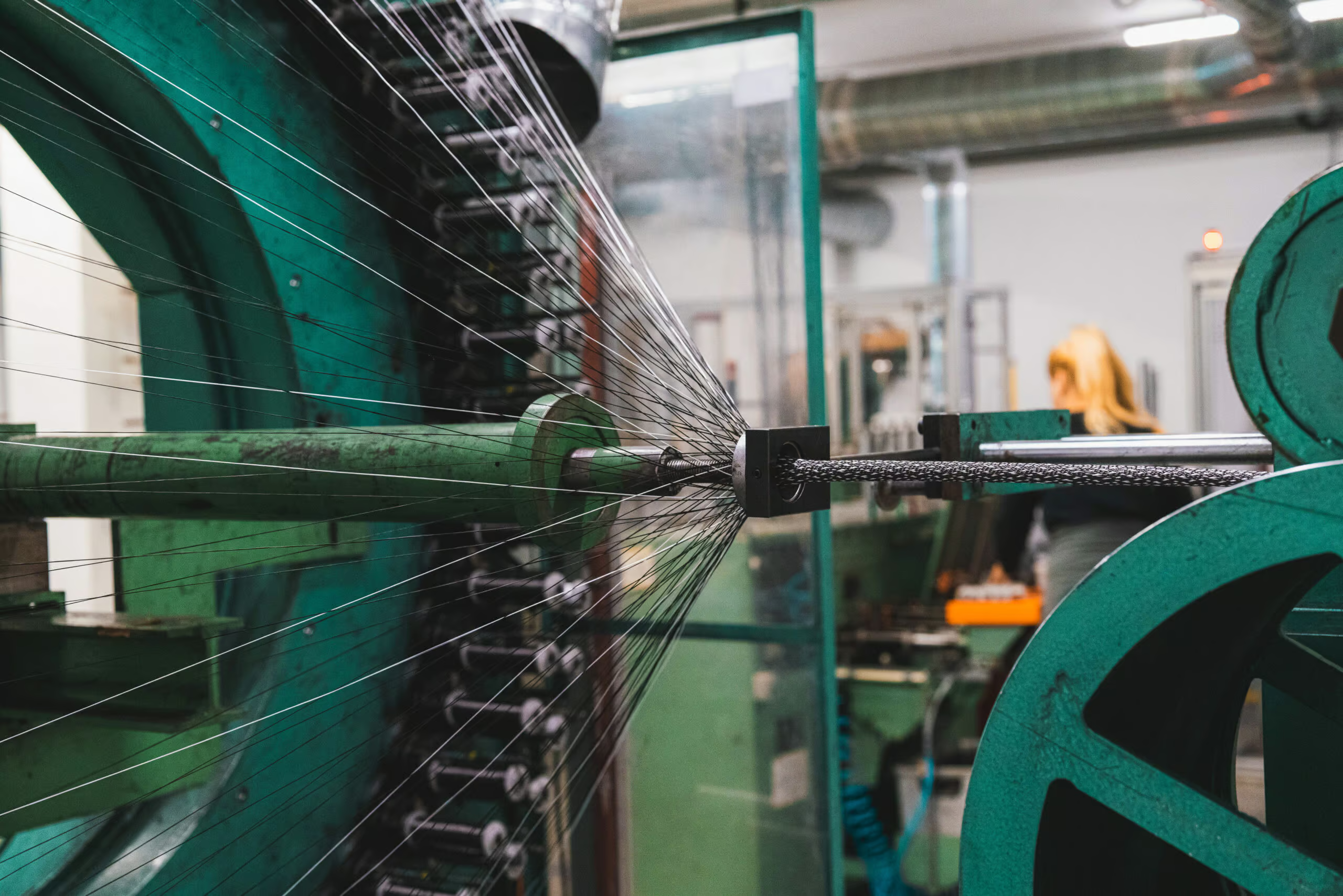

We’d better talk about that technology. “It’s very different,” he begins. “And therein lies the challenge. So much of the market says, ‘Oh, it’s a carbon fiber bike, ’ and quickly moves on to what groupset it has. But what they don’t know is that there are better ways to make a carbon fiber bike.” What Tony is referring to is Time’s use of Braided Carbon Structures, Resin Transfer Molding and Lost-Wax Core technologies, in direct contrast to the wider industry’s use of pre-preg, bladder-molded fibers – think weaving a sock from unique, individual fibers vs putting it together from pre-made sections. “What we can do with braiding is another world,” says Tony. “And that flows through to how our bikes ride, which is different and we would say, superior to any other carbon fiber bike using pre-preg technology, which is almost all of them.”

Let’s turn to that ride feel. “Well, as the carbon fiber bike industry went headfirst into extreme lightweighting, the majority of bikes out there got this really nervous feeling,” explains Tony. “Sure, they’re light, but they lost their durability and their ride quality.” Whereas, he says, a Time is incredibly stiff and reactive, “but the first time you take it down a mountain pass, you’re going to feel an incredible level of comfort.” But don’t take Tony’s word for it. “I get an email every couple of hours from someone who’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’ve had twenty-five carbon fiber bikes and where has this Time been all my life?!’” he laughs.

I tell Tony that I wish more brands talked about how their bikes handle on the descents, “It’s where you see the personality of the bike,” he says. And I agree. As a rider, you’re under pressure, the corners are coming fast, and you find yourself at the limit and not so ready to believe everything you’ve read, but are in the hot seat to feel what’s really happening under your hands, and take those inputs as the truth of the thing. How does this bike descend? It’ll tell you. “And if you have a stable, controlled feel in those situations, you’ve got something there,” adds Tony. But the nervous feeling is so well-known; is there not a risk that the timbre of a carbon fiber bike is set in the cyclist’s mind? “For sure,” agrees Tony. “And because of that, a Time is never a rider’s first or second bike. They kind of go on a journey, then they find us, and there’s this kind of homecoming, a relief. I made it! That’s the beauty of Time.”

Manufacturing stories are kind of dry. We don’t even know where our food comes from, so why would we care how our bikes are made? Just make it pretty. But just making it pretty is a pretty poor substitute for thought. Origins matter. Origins of people matter, as do those of ideas and products, like bikes, whose attributes are not measured in marketing soundbites but real sensations and nuance, and the realities of sometimes-dry manufacturing processes. “The true measure of a bike is ride quality,” says Tony. “Our job is to communicate that how we make the bikes makes a difference.”

TONY KARKLINS, TIME CEO

The roots of Time’s technology can be traced back to TVT, a brand that built some of the first composite bikes for riders such as Bernard Hinault and Greg LeMond in the Tour de France. “That tech is what got pulled into Time,” says Tony. “So we have that heritage and experience, plus, because we’re the oldest composite factory in Europe, we have people who’ve been making these bikes for decades. We’re not just sourcing labor. These are people who have been getting more and more experienced over the years.” It all adds up, he says, to a potent mix. “The Time process is highly efficient. We use a solid core, not a bladder mold, for exacting repeatability. It’s incredibly controlled. Plus, we don’t use pre-preg fiber, so we can tune the ride quality with specific strands of carbon fiber.” Which Time does via the sock-like, braided sheaths it manufactures, which they weave over the solid core, incorporating any modulus of carbon fiber and balancing any attribute, from durability to weight, in forensic detail. “Then we inject the resin into our tool, and it fills 100% of the cavity under pressure with no voids – it cannot have voids, the pressure and our solid core make that impossible. Even better, when you open the tool, our product looks beautiful, whereas a pre-preg frame takes a lot of finishing to look as good as ours does fresh out of the machine.”

The other advantage of Time’s sock-like structures is that they afford the brand granular control of each junction, curve, and shape, and allow for longer, unbroken strands of carbon fiber – the key to strength, feel, and performance. But the story gets better still. After molding, Tony says the brand melts out the solid core and reuses the material to make a new core for the next day’s production. “Our process leads to less waste, more control, and, from what we know and hear from Time customers, a really incredible ride.”

How did Tony find his way to Time, not just as the CEO but also now, as a part owner? “I’d always been a fan of the brand and loved their technology,” he says. “When Roland passed away, the Time brand was acquired by the French Rossignol Group, which also bought some other brands, such as Felt, and merged them into a bike division. I think their goal was to meld their strong ski retail presence across all these mountain towns with the bike world. Ultimately, they decided to close that project.”

As he explains, that was around the time COVID came calling. “I had some friends in the group who reached out to see if I had an interest in Time.” Why him? “They wanted to find someone who would keep the factory alive; that was very important to them, and they knew I would do that.” And not just because of Tony’s respect for the brand: he knew the value of a working, experienced composites facility. “Open a factory today and it’ll take you ten years, if you’re lucky, to produce at scale,” he says. “Time had a factory that had, at that point, been producing for over twenty years.” Plus, Tony’s wife is Slovakian. “That helped!” he laughs. “There’s definitely something in that – you go deeper. You’re sitting around a table having dinner, and you start to get the jokes and a proper sense of the culture. It felt like home.”

As Tony tells it, if the Rossignol people had been less discerning, that moment might have put an end to Time in Europe. “No doubt, that was a beautiful moment for Rossignol. How they managed that process was incredible. They wanted the factory to be preserved and grown.” As luck would have it, at the time, Tony was five years into a pre-peg project in the United States. “I knew the pain points, so the Time opportunity was a perfect segue.”

Tony’s history in the bike industry goes back forty years, with twenty in retail, and, in 2000, as the person responsible for bringing Orbea to the US, running a joint venture, Orbea US, for the next fifteen. “During that time, I got very familiar with European and global manufacturing, and saw firsthand the European factories closing and offshoring.” Tony witnessed what was a metal business turn into a composites business, a European-based industry move wholesale to the Far East. “People were like, ‘What is this new tech and how can I get it fast?’” he laughs. “Most everybody just shut down and handed everything over to three or four different manufacturers over there. I don’t think that should have happened.” Instead, Tony paints a picture of bike brands taking a beat and, perhaps slowly, figuring out how to make composite bikes. “It might have taken a minute, but in the end, they would have retained their IP, their control, their people, their company.”

After everything he’d seen, a post-Orbea Tony was keen to marry his love of the bicycle business with a course-correction. Too late for most, but not for Time, who, as we have learned, had hung on in Europe and had retained everything that made them special. It sounds like a match made in bicycle heaven. “It did all line up well,” he laughs. “And after this year’s launch of our Scylon road bike, we’re excited for what the next few seasons will bring.”

And at that, our time is up. As Tony heads off to pack for his flight, I close my laptop, grab my gear, and prepare to head out for a quick ride. I can’t help wondering what a Time would feel like. I’d better find out for myself. To the Regroup workshop!

FEATURED

Ride to a different rhythm, one born out of a distinctly European story pedigree, proven performance and a refusal to follow the expected path.