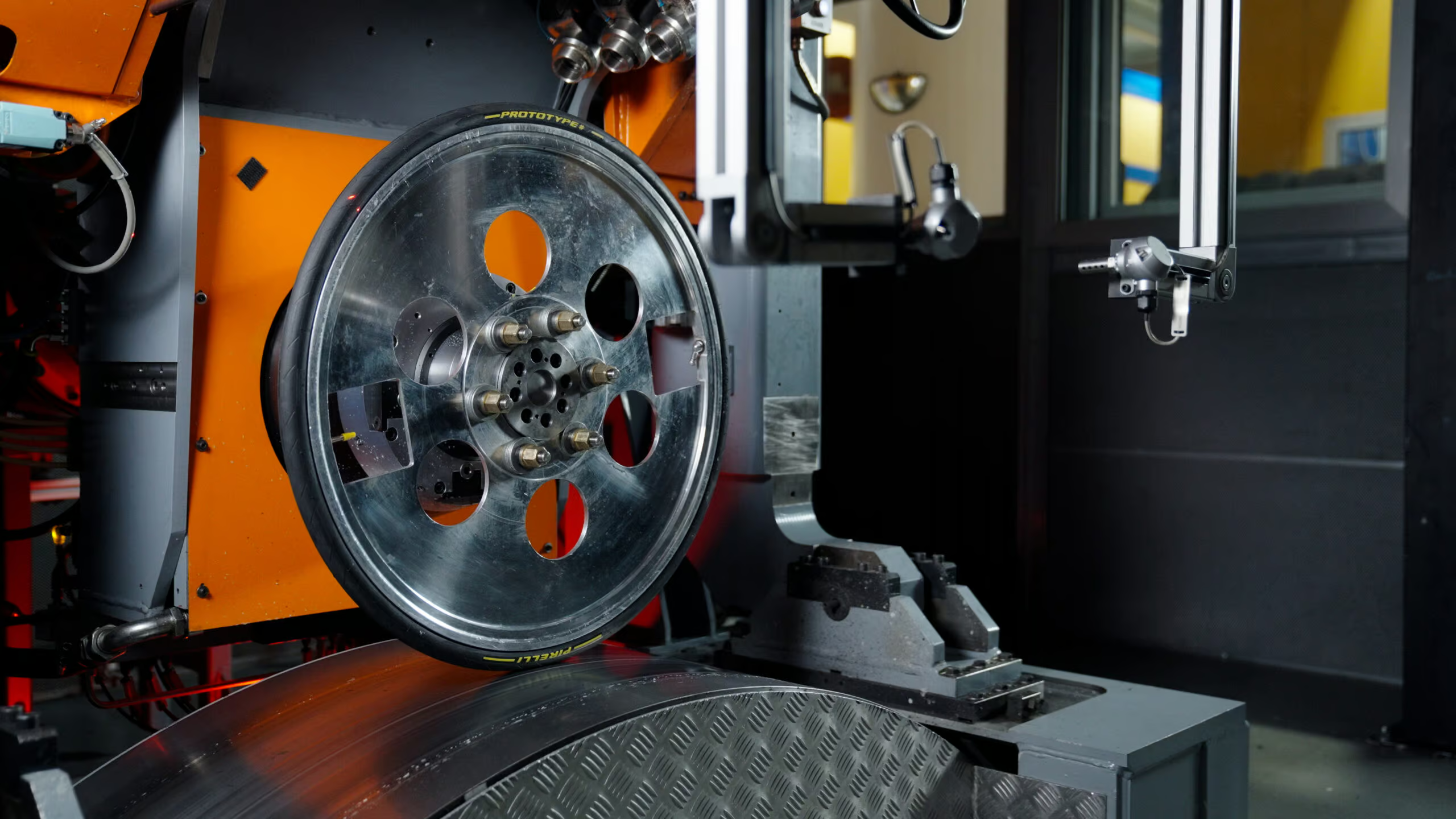

But what makes a good bike tire? Is it the rubber, the sidewalls? “First of all, I would say it’s the development methodology,” says Samuele. “And by that we mean the desired characteristics of the tire and the decisions that go into it realizing that vision. Then, balancing all of the variables and how various elements interact with each other in order to reach data and an objective performance measurement. It’s very scientific, but that’s how Pirelli works. Obviously, it’s a critical approach in sports like Formula One.”

Let’s talk about F1 for a moment. And to ask a stupid question, how different is a bike tire from a Formula One tire? “Surprisingly, not that different,” he smiles. Clearly, he’s been asked this before. “The rubber formulation is quite similar, for example. And even though the car has an engine that generates an incredible amount of torque, which places enormous mechanical stress on the rubber, the contact patch and the pressure distribution of the tire are quite large. A bicycle tire, though, has a tiny contact patch, so while the mechanical stress that goes into the tire is much less than that of a car, it’s focused on a far smaller area. Still, when you take into account the weight differential between a Formula One car and a bicycle, the total stress on the car’s tire is only around three times more than a bicycle tire.”

The next time you watch an F1 race, keep your eyes on the tires – they’re your P-Zeros, only a lot faster. “And hotter!” adds Samuele. “The working temperature of an F1 tire can exceed 120 degrees Celsius. They really only start to get going at 70 degrees. Naturally, those extremes require a formulation that can perform under such conditions.” But on the bike, even on the punchiest ride or the heaviest descent, according to Samuele, a Pirelli bicycle tire will only ever experience a temperature change of 1 or 2 degrees. “For a cyclist, the environmental temperature is much more of a factor than any stress the rider can put through their tires.”

To finish the F1 link and finally let Samuele reach the beach, I ask him whether the development that has gone into Pirelli’s bicycle tires is feeding back into the top tier of motorsport. “Hmm, we are entering an area where I cannot say much,” he says, looking serious for a moment. “Let’s just say that in areas of rolling resistance and grip, cycling is a punishing discipline that demands a lot from the tires. Those challenges offer a lot of insight that may well benefit other areas of our business.”

Intriguing stuff. But we can’t let Samuele stretch out on the lounger just yet, not without asking about the current width of bike tires, and the trend of ‘wider is better’. “Well, we were the first brand to release a road cycling, high-performance tire in 40mm width – our P-Zero,” he notes. “It became a best seller in the US after only a month. We saw the trend and pushed ahead of the demand, and we saw the market reaction. The same applies to our slick endurance tire, the Evo, which will soon be available in a 55mm variant.” Wider, though, means heavier. Is that a concern? “The reality is that in any rolling equipment, the weight is only detrimental when you have to change speed – like accelerating,” he counters. “A lightweight tire offers many benefits, but only where a change in speed is required or when the road turns upwards with a change of elevation. Once you’re at speed, the weight of your tire isn’t a factor.”

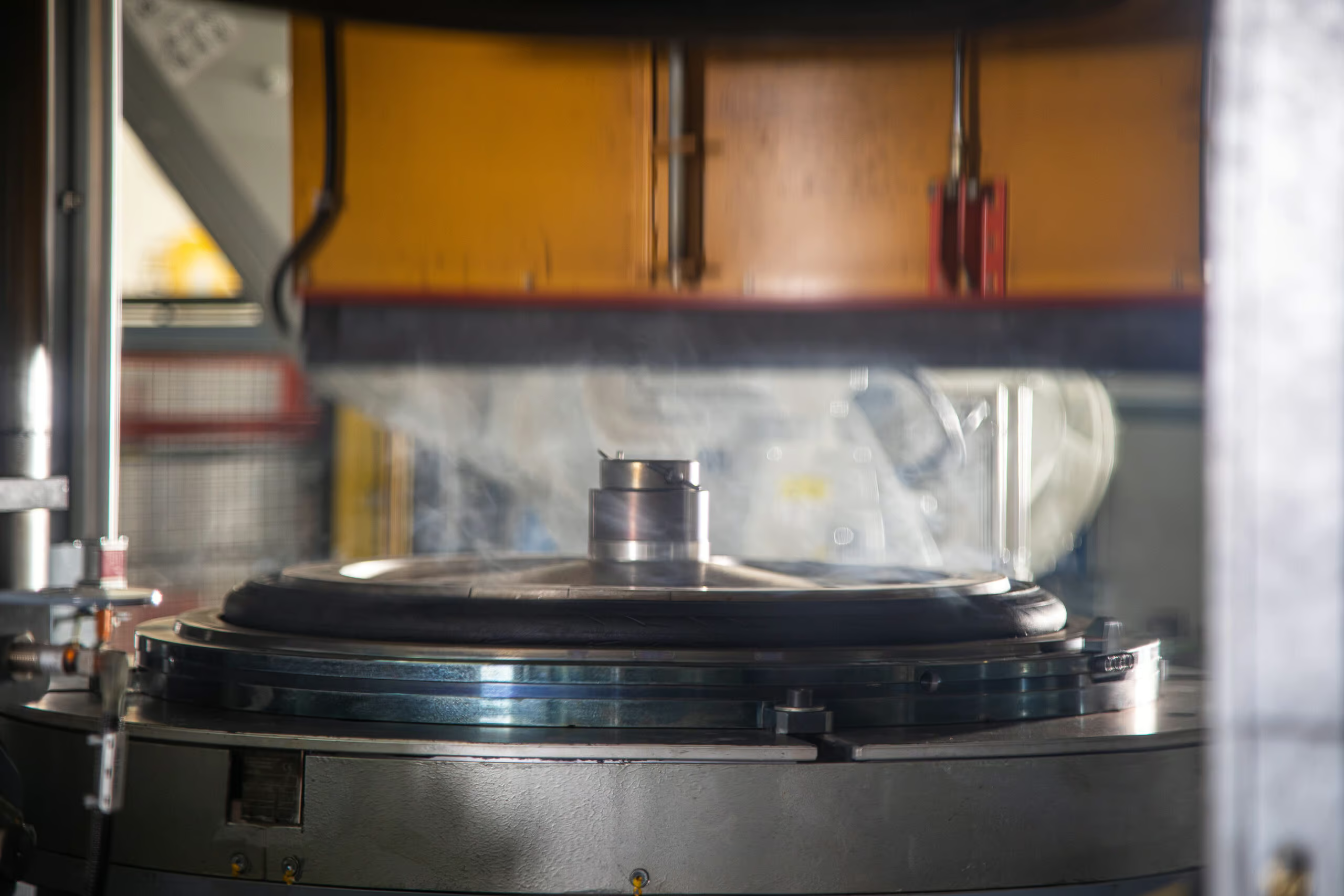

As an encore of sorts, our conversation about weight segues to puncture protection and material development. And here, Samuele has some interesting points to make. “It’s easy to forget that the rubber – the top surface of the tire – is the first line of defence against punctures,” he begins. “If we can improve the strength of the rubber so that it’s more difficult to penetrate, we can offer far higher puncture protection. And that speaks to one of Pirelli’s core differentiating points: we really go deep on the chemistry, which finds expression in material research, like blending polymers with certain attributes with other polymers in chains to create a material with vastly different characteristics, which might surface as a rubber that rolls just as well, but is far harder to penetrate.”

Ultimately, though, as Samuele neatly concludes, the soul of Pirelli is speed. “Handling is everything. If we can create a tire that invites you to greater speed because you have more confidence and control, we will have honored the Pirelli name. If we can inspire you, we have done our job!”

Consider us inspired.